Table of Contens

- Why call it Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey?

- Quick overview: The core legal rules that define Bourbon

- The Mash Bill: What grains are allowed and why it matters

- New oak only: The one-time barrel rule and its global consequences

- Aging, aromas and the palette: What new oak does to Bourbon

- Distillation: Pot stills vs. continuous column stills — what changes?

- The purity principle: Why Bourbon is often called a “whiskey purity law”

- Global effects: How Bourbon barrels shape other spirits

- Common misconceptions clarified

- How to taste Bourbon with knowledge

- Practical notes for consumers and collectors

- Why the law matters: Preservation of a style

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Conclusion: Understanding gives deeper enjoyment

Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey: A Clear Guide to America’s Most Regulated Spirit

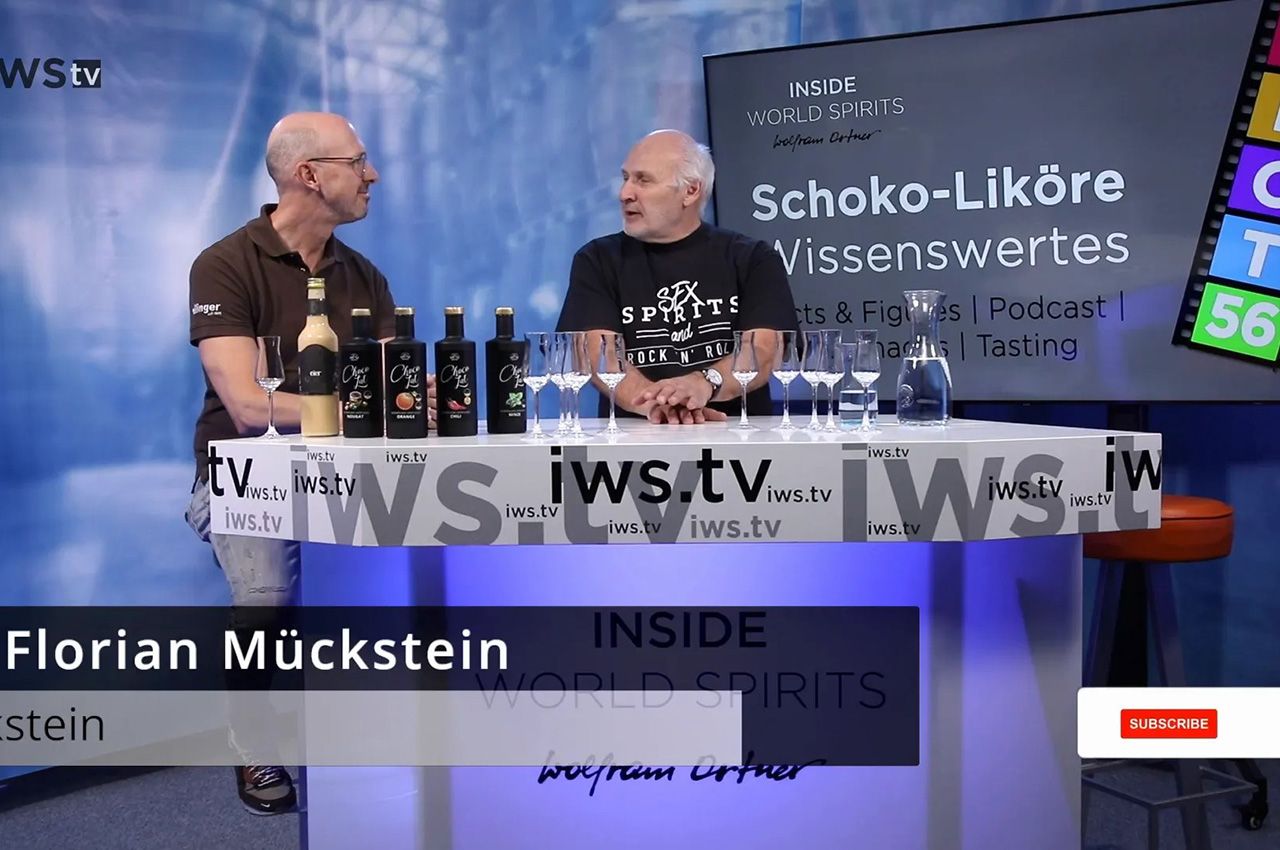

Inside World-Spirits TV host Wolfram Ortner lays out a concise, passionate explanation of why Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey is not just a style, but a tightly regulated product with legal definitions that shape everything from ingredients to barrel use. This article translates that on-screen clarity into a written guide: what the law requires, what producers can — and cannot — do, how the mash bill works, and why Bourbon’s interaction with new oak barrels is the single factor that shapes its signature aromas.

Why call it Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey?

At first glance, Bourbon seems like another regional whiskey. But the reality is different: Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey is bound by precise regulations that govern its entire identity. These laws are so prescriptive that they define production locale, grain composition, barrel requirements, strength at aging and bottling, and forbids additives that would otherwise alter the spirit. In short: Bourbon is regulated from A to Z.

Wolfram Ortner repeatedly emphasizes that those who drink Bourbon should understand what it legally represents. Knowing the constraints reveals not only the spirit’s character but also why Bourbon tastes the way it does — which is a central theme in understanding Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey.

Quick overview: The core legal rules that define Bourbon

- Made in the United States: For a whiskey to be labeled Bourbon, it must be produced in America. This geographic requirement is fundamental.

- Mash bill composition: The grain bill must contain at least 51% corn (maize).

- New oak barrels only: Bourbon must be aged in new, charred oak barrels. Used barrels are not permitted.

- Entry and bottling strength: Bourbon cannot be barreled at more than 62.5% ABV (125 proof) and must be bottled at a minimum of 40% ABV (80 proof).

- No additives: No flavorings, coloring, or sugar may be added. What you taste is the spirit and its interaction with wood and time.

The Mash Bill: What grains are allowed and why it matters

The mash bill — the mix of grains fermented to create a whiskey wash — is a defining technical and legal feature of Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey. Legally, the mash bill must contain at least 51% corn (maize). That’s the minimum threshold that makes the whiskey legally “Bourbon.”

Corn gives Bourbon its characteristic sweetness and contributes essential body and texture. But producers balance corn with other grains for flavor complexity:

- Rye: Adds spice and dryness, lending peppery or herbal notes.

- Wheat: Produces a softer, rounder profile with gentle, bready sweetness.

- Malted barley: Supplies enzymes required for fermentation and contributes malty, cereal-like aromas.

Ortner points out the mash bill is often referred to in shorthand as the “mash image” — a snapshot of the grain composition. While the law requires at least 51% corn, it also suggests practical limits: too much corn (for example, over 75%) is uncommon because corn is cheap and can unbalance the spirit, so most producers use a blend with rye or wheat plus malted barley.

There are stylistic traditions within Bourbon production. For example, a small number of distilleries favor rye-forward recipes, producing a distinctly spicier Bourbon. One example mentioned is Makers Mark (often spelled Maker's Mark), known for using wheat rather than rye, which yields a smoother, fuller-bodied profile. These choices create recognizable substyles within the strict legal framework of Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey.

New oak only: The one-time barrel rule and its global consequences

One of the most consequential legal requirements for Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey is the mandatory use of new, charred oak barrels. This single regulation explains a great deal about Bourbon’s flavor profile and its global footprint.

Why new oak? New American white oak barrels, toasted and charred, contribute intense wood-driven flavors: vanilla, caramel, toasted sugars, and a suite of compounds produced by wood degradation and charring. Because these barrels are used only once for Bourbon, the wood imparts a concentrated set of compounds into the spirit during its initial maturation.

After that one use, the barrels still retain flavorful compounds — oak tannins, residual vanillin, charred sugars — but they are considered “spent” for Bourbon production. That’s why Bourbon barrels are exported and reused across the world for aging other spirits and beers. Scotch whisky, rum producers, mezcal and tequila-makers, as well as craft brewers, prize these once-used Bourbon barrels for the distinctive Bourbon oak imprint they give to subsequent liquids.

Ortner emphasizes the scale of this phenomenon: Bourbon barrels can be found from Scotland to Mexico and beyond. Their global circulation is a direct consequence of the law requiring new oak for Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey. The barrels become a sought-after commodity for anyone who wants to borrow Bourbon’s vanilla-caramel-wood character for their own products.

Aging, aromas and the palette: What new oak does to Bourbon

Bourbon’s flavor signature is inseparable from its time in new oak. The legal insistence on new barrels creates a style that is wood-forward, but the interaction between spirit and wood produces a surprising range of aromas and flavors beyond mere oakiness.

Common aroma categories in Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey include:

- Vanilla: A hallmark derived from lignin breakdown in oak.

- Caramel and toffee: From the charring process and interaction of sugars with alcohol and heat.

- Yeast and bakery notes: From fermentation character that remains in the distillate.

- Fruit notes: Ranging from banana and stone fruit to berry-like esters, depending on fermentation and maturation.

- Spice and tannins: Especially in rye-forward mash bills or longer-aged expressions.

Bourbon can age for five, six, seven, or even eight years (and more), but the dominant influence of new oak remains. The wood doesn’t just add sweetness; it also filters and integrates flavors, tames raw distillate edges, and creates texture and weight in the mouth. Ortner notes that the most identifiable characteristic of Bourbon is its wood-forward nature — but that wood expresses itself as vanilla, caramel, and complex fruit and yeast aromas.

Distillation: Pot stills vs. continuous column stills — what changes?

Another technical variable in Bourbon production is the distillation apparatus. Producers use either continuous column stills (typical for many large Bourbon distilleries) or traditional pot stills. Each approach influences the body and character of the spirit.

- Continuous (column) stills: Often yield a lighter, cleaner distillate. They are efficient and used by many industrial-scale producers.

- Pot stills: Tend to preserve more congeners — flavor compounds that contribute body and complexity. Spirits distilled in pot stills often feel fuller and richer on the palate.

Ortner highlights that with pot still distillation, Bourbon will naturally gain more body. Yet regardless of the distillation method, the mandating factors — the mash bill, the new oak, the aging parameters — still define Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey’s overall profile. Distillation method is an important stylistic lever, but it works within the strict legal boundaries that make Bourbon recognizable.

The purity principle: Why Bourbon is often called a “whiskey purity law”

Some refer to the Bourbon regulations as a “purity law” for whiskey. That’s because, under the rules, Bourbon is not allowed to include additives such as flavorings, colorings or extra sugar. What ends up in the bottle is the fermented and distilled grain spirit, modified only by time in new oak, water to reach legal bottling proof, and nothing else.

"No flavorings, no sugar, nothing is added."

That sentence captures the spirit of the regulation. In practice, it means producers must rely on foundational processes — fermentation, distillation, the carefully chosen mash bill, barrel selection and maturation — to define the final taste. This constraint drives innovation within boundaries: distillers manipulate grain ratios, yeast strains, distillation cuts, barrel char level, warehouse selection and aging time to craft diverse Bourbons from the same legal framework.

Global effects: How Bourbon barrels shape other spirits

The one-and-only-use rule for Bourbon barrels has ripple effects worldwide. After Bourbon-filled barrels are emptied, they are a prized resource:

- Scotch whisky: Frequently finished or matured in ex-Bourbon barrels to add vanilla, honey and sweet oak layers.

- Tequila & Mezcal: Barrel-aged agave spirits (añejo and reposado) often rest in ex-Bourbon casks for added sweetness and roundness.

- Rum: Many rums are aged or finished in ex-Bourbon barrels to acquire the caramel and spice notes Bourbon oak leaves behind.

- Beer and craft spirits: Brewers and craft distillers use ex-Bourbon barrels to create stout, porter or experimental cask-aged beers and new-category spirits.

Ortner’s explanation makes clear why Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey impacts global flavor trends. The law’s insistence on new oak for American Bourbon ensures a steady supply of once-used barrels rich in the oak compounds that are useful for finishing and aging other beverages.

Common misconceptions clarified

When people hear the word “Bourbon,” several misconceptions appear. Ortner dispels some of these by stressing legal precision:

- Bourbon is not simply “whiskey from the USA.” It is whiskey made in the USA that also meets a specific legal formula.

- Used barrels mean lesser quality for Bourbon. It’s not a quality issue; it’s a legal and stylistic imperative. New oak defines Bourbon’s character. Used barrels are a resource for other categories.

- All Bourbons taste the same. Not at all. Within the strict rules, there's huge variety driven by mash bill, yeast, distillation, barrel char, warehouse climate and age.

How to taste Bourbon with knowledge

Tasting Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey becomes a more informed experience when one understands the legal background. Ortner suggests that appreciating Bourbon means recognizing the interplay of law and craft:

- Note the mash bill style: Is it corn-forward with rye spice, or wheat-softened? This hints at expected spice or roundness.

- Smell for wood-derived notes: vanilla, caramel, toasted oak — these reveal the barrel’s influence.

- Search for fruit and yeast esters: banana, stone fruit, berries, and pastry-like notes point to fermentation and yeast character.

- Assess balance: Does the wood complement or dominate the spirit? Good Bourbon integrates wood and distillate into a cohesive whole.

With this context, every sip can be enjoyed on multiple levels: technical, sensory, and historical. Ortner’s core advice is to savor Bourbon while keeping its legal and production story in mind — the laws that sound restrictive are the very things that give Bourbon its identity.

Practical notes for consumers and collectors

For consumers and collectors interested in exploring Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey, consider these practical points:

- Seek label transparency: Many producers print mash bill percentages, age statements and warehouse locations. These details help predict flavor.

- Age labels matter, but context does too: Older Bourbons may show more oak tannin and darker caramel notes. But mash bill and barrel char level also shape outcomes.

- Try a variety: Compare a rye-heavy Bourbon to a wheated Bourbon to understand how grain choices alter the profile.

- Consider finishing experiments: Some Bourbons are finished in unique casks (wine, port, or rum), though purists will note these are still subject to additive restrictions if labeled Bourbon.

Why the law matters: Preservation of a style

Legal codification does more than regulate; it preserves an identity. By defining what Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey can be, legislators and trade bodies have ensured that the category remains recognizably American and wood-driven across generations. The law prevents dilution of the category by fads and guarantees a consistent baseline for consumers who expect certain hallmark aromas and textures.

Ortner’s enthusiasm is rooted in that respect for definition. A well-made Bourbon can be celebrated precisely because it adheres to rigorous standards. The “purity” concept doesn’t restrict creativity — it channels it. Distillers innovate within rules, producing endless variety while preserving the Bourbon signature.

Key takeaways

- Bourbon must be made in the USA and contain at least 51% corn in the mash bill.

- Only new, charred oak barrels may be used for Bourbon aging — and only once.

- No additives are allowed: what is bottled is the distilled spirit and its time in wood.

- Bourbon’s primary aromas — vanilla, caramel, and complex fruit notes — are largely products of oak interaction.

- Because barrels are one-use for Bourbon, ex-Bourbon casks are widely reused globally and highly prized.

Conclusion: Understanding gives deeper enjoyment

When consumers learn the rules that govern Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey, tasting becomes more than a sensory exercise — it becomes a study of regulated craft. Wolfram Ortner’s concise explanation reminds us that those legal boundaries are not limitations but defining features: the mash bill, the new oak, the prohibition of additives, and the requirements for entry and bottling alcohol strengths are all integral to what Bourbon is.

Enjoying Bourbon with this knowledge in mind deepens appreciation. The vanilla and caramel you detect are not incidental; they are the direct result of the law that insists on new charred oak. The global demand for ex-Bourbon barrels is not accidental; it’s the downstream effect of a one-time barrel rule. Bourbon’s identity is carefully curated by both law and craftsmanship — and that’s what makes it such a fascinating and satisfying spirit.

Practical tasting checklist

Use this short checklist when you taste Bourbon to connect sensory impressions with the regulations that shape them:

- Look: note color depth (influenced by new oak).

- Nose: identify vanilla, caramel, and fruit esters.

- Palate: assess body, sweetness, and spice (mash bill clues).

- Finish: measure oak tannin and balance.

Collector quick tips

- Check labels for mash bill hints, age statements and proof.

- Remember: older doesn't always mean better — mash bill and char level matter.

- Keep bottles upright and stored in a cool, dark place to preserve character.

This supplemental content is intended for easy insertion of links later (for example, to glossary entries on "mash bill", "char level" or "age statement").

FAQ - Häufig gestellte Fragen

Yes. Bourbon can be aged for many years. Ortner mentioned whiskies that stay in the barrel five to eight years as common examples, but longer-aging Bourbons exist. Age statements, when present, should be considered alongside other factors like mash bill and barrel management.

Char level influences how deeply the wood imparts sugars and aromatic compounds into the spirit. A heavier char can intensify vanilla, caramel, and smoky notes; lighter char preserves more subtle wood tannins and spice. Producers choose char levels to shape their house style.

No. Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey forbids added flavorings and coloring. The final character must arise from the distilled spirit and its aging in new oak barrels. Water is added only to reach legal bottling strength when necessary.

The mash bill is the recipe — the proportion of grains used. At least 51% corn is required for a whiskey to be called Bourbon. Corn imparts sweetness and body; the rest of the mash bill (rye, wheat, malted barley) balances flavor and contributes complexity.

Legally, Bourbon must be aged in new, charred oak barrels. Reusing barrels for Bourbon is not permitted. This rule ensures a predictable level of wood-derived flavors. Used barrels are common for other spirits (Scotch, rum, tequila, etc.), which is why ex-Bourbon barrels are exported and reused worldwide.

No. While Kentucky is historically the heartland of Bourbon production and many iconic brands are based there, Bourbon the World’s Strictest Whiskey can be produced in any U.S. state. The legal requirement is that it must be made in the United States, not exclusively Kentucky.

Sesorisches Wissen Kompakt - IWS.TV Fibel

Can tuna with prosciutto food fusion really work? A Mediterranean Surf & Turf Recipe